The Georgian era marked the height of table etiquette in European history. There were rules to govern every aspect of eating, from how to enter the room to when to drink from one’s cup. Visitors from other countries were often dismayed by the formality and ritual required at a dinner party. Yet it was also a time of contradictions; of over-indulgence and restraint; of refinement and obscenity. Much more than simply tools for eating, Georgian table settings seem to reflect much of the social philosophy of the time.

I. Dinner Versus Everything Else

The English upper classes drew a sharp distinction between dinner and any other time when one might eat. While dinner was an extremely formal and public affair, there were few rules to govern other meals. Breakfast was generally a modest self-serve selection of pastries and fruits set out on a table for a few hours in the morning, usually from around 9am until 11am. The lady of the house might choose to have breakfast delivered to her room, so that she could avoid the necessity of appearing in public before completing her toilette (Paston-Williams, pp. 241-242).

Lunch, during the Georgian era, was a loosely-defined snack. It was referred to as “luncheon” or “nunchin” (Paston-Williams, p. 244). Since it could be eaten anywhere and was not considered a meal, there was no table setting associated with it.

Even dessert was considered distinct from the formality of dinner, although it was served immediately afterwards and at the same table. When dinner was served, it was on a long, white tablecloth. Removal of the tablecloth signalled the end of dinner and, with it, the end of formality. When dessert was served, diners could generally sit where they wished and discuss topics that would not have been polite for dinner conversation.

Yet itself was a grand affair. It might be served anytime between noon and 5pm, as dictated by the custom of the house. It would officially begin when the mistress of the house addressed the most socially prominent female present, asking her to escort the other ladies into the dining room. This would signal the master of the house to ask his most prominent guest to do the same for the men. At this point, each guest would be invited to enter in strict order of social hierarchy, segregated by gender. In this prescribed order, they would arrange themselves around the table. To seat oneself out of order would be seen as an unspeakable insult.

II. Dishes

Once seated, diners waited to be served. Dishes would not yet be on the table. In Georgian manors, kitchens were located as far as possible from the main living quarters in order to reduce the risk of fire. By the time a course reached the dining room, it would be lukewarm. For this reason, dishes were often kept in front of the fire or in specially-made warmers on the sideboard until they were needed. In this way, the food could become reheated once it was served. Similarly, wine and beer glasses were kept chilled with ice brought in from an ice well.

In Georgian England, as in other eras, dishware displayed social status. When not in use, dishes would be prominently displayed in both upper and middle class families. The material of the dishes said much about a family’s position. The wealthiest families would have dish sets of Chinese porcelain. Due to the expense and scarcity of china, many other types of porcelain and imitation porcelain were produced for use by the middle classes. Dreftware was very popular in the first half of the century. It was a white dish, often with a blue pattern (although plain white and multi-colored versions also existed). Near the end of the 18th century, Wedgwood dishes replaced Dreftware in popularity. Lower class individuals would have eaten off of pewter plates and drunk from pewter or hard leather mugs, as was common during the previous century.

III. Flatware

At the beginning of the century, guests were expected to bring their own fork, knife, and spoon. Each person carried a personal set. This custom changed as the century progressed and, by the 1750’s, guidelines for placement of flatware had been established, with forks on the left and spoons with knives on the right.

The form of flatware was also evolving during this time. Forks had been a relatively late addition to England, appearing only in the previous century; long after their introduction to other European countries. In 1619, a popular English poet named Breton echoed popular sentiment when he wrote, “we need no little forks to make hay with our mouths, to throw meat into them.” Indeed, while forks were commonplace by the early 1700’s, they still resembled tiny pitchforks. They had only two tines which were long, thin, and very sharp. They were designed only to hold meat steady while it was cut by a knife. With the introduction of these sharp forks, knives began to be made with broad, flat blades without a point at the end. This was so they could be used to scoop up food after it had been cut; something that forks of the time were not able to do. Interestingly, the loss of knife points led to the introduction of toothpicks at this same time. Prior to this, it was considered acceptable to pick one’s teeth with the point of one’s knife after a meal.

By the middle of the 18th century, forks had three tines and, by the end of the century, both forks and knives looked much as they do today.

IV. Napkins

Napkins went in and out of fashion during the Georgian era. At the beginning of this era, napkins were a prominent part of banquets and dinner parties. Often, a highly-paid specialist was hired solely to fold napkins into elaborate. A host with poorly-folded napkins was thought to lack class or character.

As the century progressed, English citizens began to look for ways to culturally distinguish themselves from the French, with whom they were at war. Abandoning napkins was considered a way to reject European influence. Instead, diners were expected to wipe their mouths on the immaculately white table cloth! By the beginning of the 19th century, this fad faded and napkins were once again an integral part of the table setting.

V. The Centerpiece

Georgian centerpieces were elaborate pieces of art, designed to display the wealth and taste of the hosts while providing a topic of conversation for guests. During the early part of the century, a basket of arranged flowers might have sufficed for a family dinner in a wealthy household. However, for a dinner party, large sugar sculptures were created from white sugar, gum paste, or almond paste and sometimes decorated with silk or placed on mirrors. These sculptures often took the form of classical Grecian temples, realistic flower arrangements, or even fresh fruit and could run the entire length of the table. There have been a few accounts of dinner parties for which the centerpieces were so elaborate that there was little room left on the table for the meal!

By the beginning of the 19th century, sugar sculptures were replaced by porcelain figurines which could be arranged in intricate pastoral scenes and, unlike sugar sculptures, had the advantage of being non-perishable.

VI. The Layout

Georgian formal dinners consisted of many courses. Diners were expected to stay in their seats while servants took away used dishes and brought new plates, bowls, and glasses with each new course of food. Diners were not expected to sample every dish. The arrangement of the dishes of food on the table was considered an art on which the mistress of the house was judged. Several books were published with maps of exactly where to place certain foods in order to create an elegant table presentation.

VII. Drinking

It’s interesting to note that guests were not allowed to drink according to their thirst. Instead, each time a guest wished to take a sip, they were required to raise their glass and “challenge” a fellow diner. This meant looking the person in the eye and waiting until they too raised their glass in acknowledgement before one could have a drink. Then the glass would be placed on the table and the diner would have to wait until he or she was challenged by someone else before being able to take another sip. If this was not enough to quench a diner’s thirst, they would simply have to wait until dessert, when the rules would be relaxed.

VIII. Contradictions

Although dinner was the most formal time of the day, representing the height of societal refinement, it was not acceptable for diners to leave the room to relieve themselves. Instead, the sideboard contained a chamber pot which would be used in plain view of all of the guests, without interrupting the conversation.

Likewise, other contradictions existed between the formal and casual. During dinner, seating was extremely formal, defining the exact social position of each guest. Diners were to enter the room in a specific order, sit in a specific arrangement, and were not to leave the table for anything. However, as soon as the meal was finished and the tablecloth removed, diners could get up and re-seat themselves wherever they wished. Even the topic of conversation changed, as it was now acceptable to speak of “coarse” subjects that would have been too rude to mention even a few minutes prior.

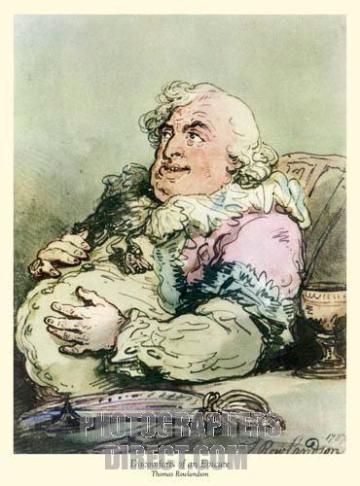

Finally, the contradiction between over-indulgence and restraint was at its height. After being presented with a carefully laid out meal, beautifully decorated table, and a performance of strict manners of restraint, diners would then stuff themselves on unheard of amounts of beef! In wealthier homes, there have been multiple records of family members averaging two pounds of beef per day, in addition to mutton, ox, pork, and fish. Breads, fruits, and vegetables were also served, but in the 18th century, nothing rivalled the popularity of beef.

Paston-Williams, S. (1999). The art of dining: A history of cooking and eating. London, England: National Trust Enterprises.

very good article. But the thing is in the middle of this writting, the word ” Dreftware” should be corrected as “Delftware” which orginally began to be produced in Delft,Netherlands since 17th Century I think.